BIRTH:

January 30, 1925 in Portland, Oregon

DEATH:

July 2, 2013 in Atherton, California

EDUCATION:

B.S. in Electrical Engineering, Oregon State University (1948); M.S. in Electrical Engineering with a specialty in Computers, University of California at Berkeley (1953); Ph.D. in Electrical Engineering with a specialty in Computers, University of California at Berkeley (1955).

EXPERIENCE:

US Navy, electronic/radar technician, WW II (1944-46); Electrical engineer, NACA Ames Laboratory, Mountain View, California (now NASA) (1948-51); Assistant Professor, electrical engineering, University of California at Berkeley (1955-56); Researcher, Stanford Research Institute (1957-59); Director, Augmentation Research Center, Stanford Research Institute (1959-77); Senior Scientist, Tymshare, Inc., Cupertino, California (1977-84); Senior Scientist, McDonnell Douglas Corporation ISG, San Jose, California (1984-89); Director, Bootstrap Project, Stanford University (1989-90); Director, Bootstrap Institute & Bootstrap Alliance (now DEI), Menlo Park, California (1990-2008).

HONORS AND AWARDS:

Over forty awards and honors, including: American Ingenuity Award (1991); IEEE Computer Pioneer Award (1993); Honorary Doctorate, Oregon State University (1994); Lemelson-MIT Prize (1997); ACM A.M. Turing Award (1997); ACM-CHI Lifetime Achievement Award (1998); IEEE John Von Neumann Medal Award (1999); USA National Medal of Technology (2000); Honorary Doctorate, Santa Clara University (2001); British Computer Society’s Lovelace Medal (2001); Norbert Wiener Award for Professional and Social Responsibility (2005).

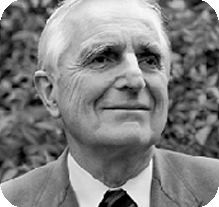

Douglas Engelbart

For an inspiring vision of the future of interactive computing and the invention of key technologies to help realize this vision.

The first error people make about Doug Engelbart is to confuse him with a computer scientist. He is not a computer scientist, but an engineer by training and an inventor by choice. His numerous technological innovations (including the computer mouse, hypertext, and the split screen interface) were crucial to the development of personal computing and the Internet. His work helped to change the way computers work, from specialized machinery that only trained technicians could use, to a medium designed to augment the intelligence of its users and foster their collaboration. In every text, conference talk, and media appearance for the past fifty years, this stubborn man, this hopeful man, has constantly repeated the same thing:

As human matters are getting increasingly complex and urgent, long terms solution will more likely come through the development of more powerful problem solving tools than through piecemeal solutions on specific problems.

Attempting to solve these ever more complex/urgent problems with the help of computer hardware and software has been the story of Douglas Engelbart’s professional life, his “crusade”.

Douglas C. Engelbart was born in Portland, Oregon, in 1925, the second of three children of a couple of Scandinavian and German descent. His father was an electrical engineer who owned a radio shop until he died (when Douglas was nine years old). He graduated from high school in 1942, and went on to study Electrical Engineering at Oregon State University, where he was trained as a radar technician, before he was drafted into the military in 1944. The radar training proved to be central for the rest of his career, and first triggered an absolute fascination in his young mind. He was in the Navy from 1944 to 1946, and was stationed for a year at the Philippines Sea Frontier, in the Manila bay. During that year he read Vannevar Bush's As We May Think article—a crucial influence on his later work. After the war, he went back to university in Corvallis, Oregon to finish his degree in Electrical Engineering. He graduated in 1948, and then took a job in California at the Ames Navy Research Center, where he stayed for 3 years.

Douglas Engelbart's decision to get involved in computing research happened in a complex move that encompassed most aspects of his personal and professional life. Engelbart identifies with a specific American generation, the depression kids—a generation born in adverse conditions that came of age during World War II. The war had left these kids in a paradoxical situation where science and technology had been the key to a Pyrric victory, and where an idealistic opening of new era was both full of hopes and fears, including a moral obligation to prevent such events to ever happen again. This paradoxical situation implied a specific way to situate oneself, in respect to ambivalent feelings and goals, toward the general good of mankind, best expressed in Engelbart’s military-religious metaphor of his crusade for the augmentation of human intellect.

Engelbart decided to go to graduate school at Berkeley, where he earned his Ph.D. in electrical engineering in 1955 (John Woodyard was his advisor). This degree at Berkeley had reinforced his commitment to his crusade but had not provided him, at least directly, with the means to research and implement his ideas. He decided to form a corporation, Digital Techniques, to capitalize on his Ph.D. work on gas discharge devices. The experience did not last long as Digital Techniques closed down in 1957 after an assessment report from a team of experts concluded that solid state devices would soon doom their project.

Engelbart joined Stanford Research Institute (SRI, now Stanford Research International) in the Summer of 1957. SRI provided him with an environment best suited for the implementation of his Research Center for the Augmentation of Human Intellect (ARC), which soon became the source of many crucial hardware and software innovations such as: the mouse, integrated email, display editing, windows, cross-file editing, idea/outline processing, hypermedia, shared-screen teleconferencing, online publishing, and groupware—all integrated into their oN-Line System (NLS hereafter). Demonstrated for the first time in the famous May,1968 Mother of All Demos in San Francisco, NLS was designed to allow Computer-Supported Collaborative Work (CSCW), a field he essentially created.

Engelbart’s strategic vision began with the recognition of a major reason why some large-scale problems continue to elude humankind’s best efforts. His radical scale change principle asserts that as a complex system increases in scale, it changes not only in size but also in its qualities. This principle, in fact one of the three basic laws of Hegelian dialectic, seems at odds with the common-sense view that large-scale systems are reducible to smaller-scale parts without loss of qualities. Even if Engelbart knew that the computer was just another artifact at a time when more engineering was not necessarily the solution, he also knew that this specific language artifact was offering unusual characteristics. He understood that the computer was opening the cognitive realm to more dimensions than the usual three, allowing non-linear thinking. But, most importantly, it was extremely fast; it could calculate, display and help organize ideas at a blazing speed. He realized that the introduction of the computer, as a powerful auxiliary to human intellect, could turn a quantitative change into a qualitative change. Facing numerous too urgent and complex problems, the little inelastic mind of the human being could, with the augmentation of the computer, become up to the challenge. Most importantly, this basic tenet of his philosophy ended up playing as important of part in the human system as in the tool system.

That the existence of a critical mass of augmented humans necessary to bootstrap, and thus augment the whole species, afforded no doubt in Engelbart’s mind. That is, in essence, what his notion of co-evolution between man and computer, tool system and human system, means. Human beings need a methodology and training that organizes their efforts at the levels of scale that are appropriate to the problems they are trying to solve. His intellect augmentation is such a method. The method provides a human-centered design for information technology that stands in contrast to the common automation approach to technology. In the automation approach, technology serves to replace human effort, thus saving time and freeing users to concentrate on more important matters. Automation, like Artificial Intelligence, does not alter the fundamental capabilities of the human users. In contrast, Engelbart’s intellect augmentation provides a model of technology that is deliberately designed so that human abilities will increase in response to using it.

An excellent example of intellect augmentation is the computer mouse (U.S. Patent # 3,541,541). Prior to Engelbart’s x-y position indicator, computer input was entered as symbols via keyboards or punch cards. The mouse allows a direct manipulation of elements within the computer environment and thus crosses the physical boundary between human and computer. It makes the interface an extension of human action rather than a mediator between the human and the machine. It extends, or augments, a very basic human ability, two-dimensional hand movement, into the ability to manipulate digital media. All of Engelbart’s efforts aim at extension of human capabilities in combination with technological innovation. The result is not merely people who have less to do thanks to the machine (automation) but people who have abilities to do more with the machine (augmentation).

Engelbart slipped into relative obscurity after 1976 due to various misfortunes and misunderstandings. Several of Engelbart's best researchers had become alienated from him and left his organization when Xerox PARC was created in 1970. The Mansfield Amendment, the end of the Vietnam War, and the end of Project Apollo reduced his funding from ARPA and NASA. SRI's management, which did not understand what he was trying to accomplish, fired him in 1976. In 1978, a company called Tymshare bought NLS, hired him as a Senior Scientist, and offered commercial services based upon NLS. Engelbart soon found himself marginalized and relegated to obscurity—operational concerns superseded his desire to do further research. Various executives at Tymshare and McDonnell Douglas (which took over Tymshare in 1982) expressed interest in his ideas, but never committed the funds or the people to further develop them. He left McDonnell Douglas in 1986.

Since the mid 1990s, several important prizes and awards have recognized the seminal importance of Engelbart's contributions: In 1996 he was awarded the Yuri Rubinsky Memorial Award; in 1997 the Lemelson-MIT Prize, the world's largest single prize for invention and innovation, and the Turing Award. In 1999 Paul Saffo, from the Institute for the Future, hosted a large symposium at Stanford University's Memorial Auditorium, to honor Engelbart and his ideas. In December 2000 he was awarded the American National Medal of Technology, and in 2001 he was awarded the British Computer Society's Lovelace Medal.

Until his death in 2013 he served as the director emeritus of the Douglas Engelbart Institute (formerly Bootstrap Institute), which he founded in 1988 with his daughter, Christina Engelbart. It is located in Fremont, California and promotes the latest refinement of his philosophy, the concept of Collective IQ, and development of what he called Open Hyper-Document Systems (OHS), and HyperScope, a subset of OHS.

Additional Links

Douglas Engelbart Institute: http://dougengelbart.org/

Stanford University MouseSite: http://sloan.stanford.edu/MouseSite/MouseSitePg1.html

Video of the 1968 Demo: http://www.archive.org/details/XD301_69ASISconfPres_Reel1

Stanford Oral History interviews by Henry Lowood and Judy Adams, edited by Thierry Bardini: http://www-sul.stanford.edu/depts/hasrg/histsci/ssvoral/engelbart/engfmst1-ntb.html

Frode Hegland & Fleur Klijnsma, Invisible Revolution: The Doug Engelbart Story, a web documentary: http://www.invisiblerevolution.net/

Author: Thierry Bardini

THE A.M. TURING AWARD

THE A.M. TURING AWARD